Phoenician Art Particularly Was Among the Most Sought After in the Ancient World

Phoenicia was an ancient Semitic-speaking thalassocratic civilisation that originated in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modernistic Lebanon.[i] [2] At its height between 1100 and 200 BC, Phoenician civilization spread across the Mediterranean, from Cyprus to the Iberian Peninsula.

The Phoenicians came to prominence post-obit the collapse of almost major cultures during the Late Statuary Age. They developed an expansive maritime trade network that lasted over a millennium, becoming the dominant commercial power for much of classical artifact. Phoenician trade also helped facilitate the exchange of cultures, ideas, and knowledge between major cradles of culture such as Hellenic republic, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. After its zenith in the 9th century BC, Phoenician civilization in the eastern Mediterranean slowly declined in the face of foreign influence and conquest, though its presence would remain in the central and western Mediterranean until the 2nd century BC.

Phoenician civilization was organized in city-states, similar to those of ancient Greece, of which the most notable were Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos.[3] [iv] Each city-state was politically independent, and there is no testify the Phoenicians viewed themselves every bit a single nationality.[5] Carthage, a Phoenician settlement in northwest Africa, became a major civilization in its ain right in the 7th century BC.

Since little has survived of Phoenician records or literature, near of what is known about their origins and history comes from the accounts of other civilizations and inferences from their fabric culture excavated throughout the Mediterranean Body of water.

Origins [edit]

Herodotus believed that the Phoenicians originated from Bahrain,[6] [7] a view shared centuries after past the historian Strabo.[eight] This theory was accustomed by the 19th-century German classicist Arnold Heeren, who noted that Greek geographers described "two islands, named Tyrus or Tylos, and Aradus, which boasted that they were the mother country of the Phoenicians, and exhibited relics of Phoenician temples."[9] The people of modern Tyre in Lebanon, have particularly long maintained Persian Gulf origins, and the similarity in the words "Tylos" and "Tyre" has been commented upon.[x] The Dilmun civilisation thrived in Bahrain during the period 2200–1600 BC, as shown by excavations of settlements and the Dilmun burial mounds. Withal, some scholars annotation that at that place is fiddling bear witness Bahrain was occupied during the time when such migration had supposedly taken place.[11] Genetic research from 2017 showed that "present-mean solar day Lebanese derive most of their beginnings from a Canaanite-related population, which therefore implies substantial genetic continuity in the Levant since at least the Bronze Age" based on ancient DNA samples from skeletons establish in modern-24-hour interval Lebanon.[12] However, this study did non look at Arabian genetic history, and an even more recent study highlighted the high relatedness of Arabians with littoral Levantines, showing that Arabian hunter-gatherers derive nearly of their beginnings from Neolithic Levantines, and that modern inhabitants of the UAE derive a greater corporeality of their ancestry from Neolithic Levantines than exercise modern Levantines. While mod Lebanese derive over 90% of their beginnings from Bronze Age Sidonians, Emiratis derive 75% of their DNA from Bronze Age Sidon in Lebanon and 25% from Arabian hunter-gatherers who were highly related to the Natufians, or Neolithic Levantines.[13] Therefore any dorsum-migration of Arabians to the Levant is difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish genetically.

Cover of a Phoenician anthropoid sarcophagus of a adult female, made of marble, 350–325 BC, from Sidon, at present in the Louvre.

Certain scholars suggest there is enough prove for a Semitic dispersal to the fertile crescent circa 2500 BC. By contrast, other scholars, such as Sabatino Moscati, believe the Phoenicians originated from an admixture of previous non-Semitic inhabitants with the Semitic arrivals. Nonetheless, in reality, the ethnogenesis of the Canaanites, and more specifically, Phoenicians, is much more complex. The Canaanite culture that gave rise to the Phoenicians apparently developed in situ from the before Ghassulian chalcolithic culture. Ghassulian itself adult from the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, which in turn developed from a fusion of their ancestral Natufian and Harifian cultures with Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) farming cultures, practicing the domestication of animals during the 6200 BC climatic crisis, which led to the Neolithic Revolution in the Levant.[14] Byblos is attested as an archaeological site from the Early Statuary Age. The Late Bronze Age country of Ugarit is considered quintessentially Canaanite archaeologically,[fifteen] even though the Ugaritic linguistic communication does not belong to the Canaanite languages proper.[16] [17]

Emergence during the Belatedly Bronze Age (1550–1200 BC) [edit]

In the early on 16th century BC, Egypt ejected foreign rulers known as the Hyksos, a various group of peoples from the Near East, and re-established native dynastic rule under the New Kingdom. This precipitated Arab republic of egypt's incursion into the Levant, with a item focus on Phoenicia; the first known account of the Phoenicians relates to the conquests of Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC). Littoral cities such as Byblos, Arwad, and Ullasa were targeted for their crucial geographic and commercial links with the interior (via the Nahr al-Kabir and the Orontes rivers). The cities provided Egypt with admission to Mesopotamian trade equally well equally abundant stocks of the region's native cedar wood, of which there was no equivalent in the Egyptian homeland. Thutmose 3 reports stocking Phoenician harbors with timber for annual shipments, also every bit constructing ships for inland merchandise through the Euphrates River.[18]

Co-ordinate to the Amarna Letters, a serial of correspondences between Egypt and Phoenicia from 1411 to 1358 BC, by the mid 14th century, virtually of Phoenicia, along with parts of the Levant, came under a "loosely divers" Egyptian administrative framework. The Phoenician urban center states were considered "favored cities" to the Egyptians, helping ballast Egypt's access to resources and trade. Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, and Byblos were regarded equally the well-nigh important. Though nominally under Egyptian rule, the Phoenicians had considerable autonomy and their cities were fairly well developed and prosperous. They are described as having their own established dynasties, political assemblies, and merchant fleets, even engaging in political and commercial competition among themselves. Byblos was obviously the leading city exterior Arab republic of egypt proper, accounting for virtually of the Amarna communications. It was a major middle of bronze-making, and the master terminus of precious goods such as tin can and lapis lazuli from equally far east as Afghanistan. Sidon and Tyre besides commanded interest among Egyptian officials, beginning a pattern of rivalry that would span the next millennium.

The economic dynamism of Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty, particularly nether its ninth pharaoh, Amenhotep III (1391–1353 BC), brought further prosperity and prominence to the Phoenician cities. In that location was growing demand for a broad array of goods, though timber remained the chief article: Egypt's expanding shipbuilding industry and rapid construction of temples and estates were a driving force of the economic system; cedar was the wood of pick for the coffins of the priestly and upper form. Initially dominated by Byblos, nearly every city had access to a variety of hardwood, with the notable exception of Tyre. Every city saw an influx of wealth and a more diversified economy that included loggers, artisans, traders, and sailors.

Hittite intervention and Late Bronze Age collapse [edit]

The Amarna messages report that from 1350 to 1300 BC, neighboring Amorites and Hittites were capturing Phoenician cities, specially in the n. Arab republic of egypt afterwards lost its littoral holdings from Ugarit in northern Syria to Byblos near central Lebanon. The southern Phoenician cities appeared to have remained autonomous, though under Seti I (1306–1290 BC) Egypt reaffirmed its control.

Some time betwixt 1200 and 1150 BC, the Tardily Statuary Age collapse severely weakened or destroyed virtually civilizations in the region, including the Egyptians and Hittites.

Ascendance and high betoken (1200–800 BC) [edit]

The Phoenicians, now free from foreign domination and interference, appeared to have weathered the crisis relatively well, emerging as a distinct and organized civilization in 1230 BC, shortly after the approximate transition to the Fe Age (c. 1200–500 BC). For the next several centuries, Phoenicia was prosperous, and the menstruum is sometimes described as a "Phoenician renaissance."[19] They filled the ability vacuum acquired by the Late Bronze Age plummet by becoming the sole mercantile and maritime ability in the region, a status they would maintain for the next several centuries.[20]

Byblos and Sidon were the earliest powers, though the relative prominence of Phoenician metropolis states would ebb and flow throughout the millennium. Other major cities were Tyre, Simyra, Arwad, and Berytus, all of which appeared in the Amarna tablets of the mid-second millennium BC. Byblos was initially the main point from which the Phoenicians dominated the Mediterranean and Red Bounding main routes. It was hither that the showtime inscription in the Phoenician alphabet was plant, on the sarcophagus of Male monarch Ahiram (c. 850 BC).[21] Phoenicia'southward independent coastal cities were ideally suited for trade betwixt the Levant area, which was rich in natural resources, and the rest of the ancient world.

Early into the Iron Age, the Phoenicians established ports, warehouses, markets, and settlement all across the Mediterranean and up to the southern Black Sea. Initially led by Tyre, colonies were established on Cyprus, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, Sicily, and Malta, as well every bit the fertile coasts of North Africa and the mineral rich Iberian Peninsula. Though disputed, some scholars believe Carthage, which would afterwards emerge equally a major power in the western Mediterranean, was founded during the reign of Pygmalion of Tyre (831–735 BC).[22] The Phoenician'due south complex mercantile network supported what Fernand Braudel calls an early example of a "world-economy", described as "an economically democratic department of the planet able to provide for nigh of its ain needs" due to links and exchanges provided by the Phoenicians.[23]

A unique concentration in Phoenicia of silver hoards dated some time during its loftier point contains hacksilver (used for currency) that bears lead isotope ratios matching ores in Sardinia and Spain.[24] This metal evidence indicates the extent of Phoenician merchandise networks. It likewise seems to confirm the Biblical testament of a western Mediterranean port city, Tarshish, supplying King Solomon of Israel with silver via Phoenicia.[25]

The offset textual account of the Phoenicians during the Iron Age comes from Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser I, who recorded his campaign against the Phoenicians between 1114 and 1076 BC.[twenty] Seeking access to the Phoenician's high quality cedar wood, he describes exacting tribute from the leading cities at the time, Byblos and Sidon. Roughly a twelvemonth later, the Egyptian priest, Wenamun describes his efforts to procure cedar forest for a religious temple from 1075 to 1060 BC.[26] [Note 1] Contradicting the business relationship of Tiglath-Pileser I, Wenamun describes Byblos and Sidon as impressive and powerful coastal cities, which suggests that the Assyrian siege was ineffectual. Although once vassals of the Egyptians during the Bronze Age, the city states were now able to reject Wenamun's demand for tribute, instead forcing the Egyptians to agree to a commercial system.[26] This indicates the extent to which the Phoenicians had get a more influential and contained people.

The drove of urban center states constituting Phoenicia came to be characterized by outsiders, and even the Phoenicians themselves, by one of the dominant states at a given time. For many centuries, Phoenicians and Canaanites alike were alternatively called Sidonians or Tyrians. Throughout much of the 11th century BC, the biblical books of Joshua, Judges, and Samuel use the term Sidonian to depict all Phoenicians; by the 10th century BC, Tyre rose to become the richest and most powerful Phoenician city land, particularly during the reign of Hiram I (c. 969–936 BC). Described in the Jewish Bible as a contemporary of kings David and Solomon of State of israel, he is best known for being commissioned to build Solomon's Temple, where the skill and wealth of his city state is noted.[27] Overall, the Old Testament references Phoenician city states—namely Sidon, Tyre, Arvad (Awad) and Byblos—over 100 times, indicating the extent to which Tyrian and Phoenician culture was recognized.[28]

Indeed, the Phoenicians stood out from their contemporaries in that their ascension was relatively peaceful. As archeologist James B. Pritchard notes, "They became the first to provide a link between the culture of the ancient Near East and that of the uncharted world of the West…They went not for conquest as the Babylonians and Assyrians did, just for merchandise. Profit rather than plunder was their policy."[29] Pritchard observes that fifty-fifty the Israelites, who were in disharmonize with almost every neighboring culture, seemed to regard the Phoenicians every bit "respected neighbors with whom Israel was able to maintain amicable diplomatic and commercial relations throughout a span of a half millennium … Nevertheless despite the ideological differences betwixt Israel and her northern neighbors, detente prevailed."[28]

The Nora Stone, found in Sardinia, Italy in the 18th century, is the most ancient Phoenician inscription ever institute exterior the Phoenician heartland (c. 8th-9th century BC). It is indicative of the expansive trade network the Phoenicians established in ancient times. National Archaeological Museum, Cagliari, Italy.

During the rule of the priest Ithobaal (887–856 BC), Tyre expanded its territory as far due north equally Beirut (incorporating its sometime rival Sidon) and into office of Republic of cyprus; this unusual human activity of aggression was the closest the Phoenicians ever came to forming a unitary territorial state. Tellingly, once his realm reached its greatest territorial extent, Ithobaal alleged himself "Rex of the Sidonians", a title that would be used by his successors and mentioned in both Greek and Jewish accounts.[26]

Phoenician alphabet [edit]

During their loftier point, specifically effectually 1050 BC,[17] the Phoenicians developed a script for writing Phoenician, a Northern Semitic linguistic communication. They were amid the first state-level societies to make all-encompassing use of alphabets. The family of Canaanite languages, spoken by Israelites, Phoenicians, Amorites, Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites, was the beginning historically attested group of languages to use an alphabet to record their writings, based on the Proto-Canaanite script. The Proto-Canaanite script, which is derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs, uses around 30 symbols but was not widely used until the rise of new Semitic kingdoms in the 13th and 12th centuries BC.[30]

The Canaanite-Phoenician alphabet consists of 22 letters, all consonants.[31] It is believed to be one of the ancestors of modern alphabets.[32] [33] Through their maritime trade, the Phoenicians spread the use of the alphabet to Anatolia, North Africa, and Europe, where it likely served the purpose of communication and commercial relations.[20] The alphabet was adopted by the Greeks, who developed it to have singled-out letters for vowels as well as consonants.[34] [35]

The name Phoenician is by convention given to inscriptions beginning around 1050 BC, because Phoenician, Hebrew, and other Canaanite dialects were largely duplicate before that time.[17] [36] The so-called Ahiram epitaph, engraved on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram from about 1000 BC, shows a fully adult Phoenician script.[37] [38] [39]

Acme and gradual reject (900–586 BC) [edit]

The Belatedly Iron Age saw the height of Phoenician shipping, mercantile, and cultural action, particularly betwixt 750 and 650 BC.[20] Phoenician influence was visible in the "Orientalization" of Greek cultural and artistic conventions through Egyptian and Virtually Eastern influences transmitted by the Phoenician. The infusion of various technological, scientific, and philosophical ideas from all over the region laid the foundations for the emergence of classical Hellenic republic in the fifth century BC.[20]

The Phoenicians, already well known as peerless mariners and traders, had also developed a distinct and circuitous culture. They learned to manufacture both common and luxury goods, becoming "renowned in antiquity for clever trinkets mass produced for wholesale consumption."[40] They were proficient in glass-making, engraved and chased metalwork (including statuary, iron, and gold), ivory etching, and woodwork. Amongst their well-nigh pop appurtenances were fine textiles, typically dyed with the famed Tyrian purple. Homer's Iliad, which was composed during this period, references the quality of Phoenician clothing and metal goods.[20] Phoenicians also became the leading producers of glass in the region, with thousands of flasks, beads, and other glassware existence shipped across the Mediterranean.[41] Colonies in Spain appeared to have utilized the potter's wheel,[42] while Carthage, now a nascent city state, utilized series production to produce large numbers of ships quickly and cheaply.[43]

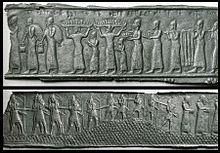

Two statuary fragments from an Assyrian palace gate depicting the drove of tribute from the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon (859–824 BC). British Museum.

Vassalage under the Assyrians (858–608 BC) [edit]

As a mercantile power concentrated along a narrow littoral strip of land, the Phoenicians lacked the size and population to support a big military. Thus, as neighboring empires began to ascent, the Phoenicians increasingly fell under the sway of foreign rulers, who to varying degrees confining their autonomy.[26]

The Assyrian conquest of Phoenicia began with King Shalmaneser III, who rose to power in 858 BC and began a series of campaigns against neighboring states. The Phoenician city states cruel under his dominion over a catamenia of three years, forced to pay heavy tribute in money, appurtenances, and natural resource. Even so, the Phoenicians were not annexed outright—they remained in a country of vassalage, subordinate to the Assyrians but immune a certain caste of freedom. Relative to other conquered peoples in the empire, the Phoenicians were treated well, due to a history of otherwise amicable relations with the Assyrians, and to their importance as a source of income and fifty-fifty affairs for the expanding empire.[26]

Later the death of Shalmaneser Iii in 824 BC, the Phoenicians maintained their quasi-independence, as subsequent rulers did not wish to meddle in their internal diplomacy, lest they deprive their empire of a key source of upper-case letter. This inverse in 744 BC, with the ascension of Tiglath-Pileser Three, who sought to forcefully comprise surrounding territories rather than keep them subordinate. By 738 BC, nearly of the Levant, including northern Phoenicia, were annexed and roughshod straight under Assyrian administration; only Tyre and Byblos, the most powerful of the city states, remained as tributary states exterior of straight control.

Within years Tyre and Byblos rebelled. Tiglath-Pileser III quickly subdued both cities and imposed heavier tribute. After several years, Tyre rebelled again, this time allying with its erstwhile rival Sidon. After two to three years, Sargon Ii (722–705 BC) successfully besieged Tyre in 721 BC and crushed the alliance. In 701 BC, his son and successor Sennacherib suppressed further rebellions across the region, reportedly deporting virtually of Tyre's population to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. During the seventh century BC, Sidon rebelled and was completely destroyed by Esarhaddon (681–668 BC), who enslaved its inhabitants and built a new city on its ruins.

While the Phoenicians endured unprecedented repression and conflict, by the cease of the 7th century BC., the Assyrians had been weakened past successive revolts throughout their empire, which made led to their destruction by the Iranian Median Empire.

Babylonian rule (605–538 BC) [edit]

The Babylonians, formerly vassals of the Assyrians, took advantage of the empire's plummet and rebelled, quickly establishing the Neo-Babylonian Empire in its place. The decisive boxing of Carchemish in northern Syria ended the historic hegemony of the Assyrians and their Egyptian allies over the Near East. While Babylonian rule over Phoenicia was brief, it hastened the abrupt turn down that began under the Assyrians. Phoenician cities revolted several times throughout the reigns of the start Babylonian king, Nabopolassar (626–605 BC), and his son Nebuchadnezzar Ii (c. 605–c. 562 BC). The latter's tenure witnessed several regional rebellions, especially in the Levant. After suppressing a defection in Jerusalem, Nebuchadnezzar besieged the rebellious Tyre, which resisted for thirteen years from 587 to 574 BC. The urban center ultimately capitulated nether "favorable terms".[44]

During the Babylonian period, Tyre briefly became "a republic headed by elective magistrates",[45] adopting a arrangement of government consisting of a pair of judges, known equally sufetes, who were chosen from the most powerful noble families and served brusque terms.[46]

Western farsi period (539–332 BC) [edit]

The conquests of the late Iron Age left the Phoenicians politically and economically weakened, with urban center states gradually losing their influence and autonomy in the face of growing foreign powers. Nevertheless, during virtually of the iii centuries of vassalage and domination by Mesopotamian powers the Phoenicians generally managed to remain relatively independent and prosperous. Even when conquered, many of the city states continued to flourish, leveraging their role equally intermediaries, shipbuilders, and traders for one strange suzerain or another.[26] This pattern would go on through the roughly two centuries of Western farsi rule.

In 539 BC, Cyrus the Bang-up, male monarch and founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, had exploited the unraveling of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and took the upper-case letter of Babylon.[47] As Cyrus began consolidating territories across the Near East, the Phoenicians obviously fabricated the pragmatic calculation of "[yielding] themselves to the Persians."[48] Most of the Levant was consolidated past Cyrus into a single satrapy (province) and forced to pay a yearly tribute of 350 talents, which was roughly half the tribute that was required of Arab republic of egypt and Great socialist people's libyan arab jamahiriya. This connected the tendency, which began under the Assyrians, of the Phoenicians being treated with a relatively lighter hand by most rulers.[49]

In fact, the area of Phoenicia was later divided into 4 vassal kingdoms—Sidon, Tyre, Arwad, and Byblos—which were allowed considerable autonomy. Unlike in other areas of the empire, including adjacent Jerusalem and Samaria, in that location is no tape of Persian administrators governing the Phoenician city-states. Local Phoenician kings were allowed to remain in power and even given the same rights as Western farsi satraps (governors), such as hereditary offices and minting their own coins.[47] The otherwise decentralized nature of Persian administration meant the Phoenicians, though no longer an contained and influential power, could at least continue to deport their political and mercantile affairs with relative freedom.[50]

Coin of Abdashtart I of Sidon during the Achaemenid period. He is depicted behind the Persian king on the chariot.

Even so, during the Farsi era, many Phoenicians left to settle elsewhere in the Mediterranean, particularly farther west; Carthage was a pop destination, every bit past this point it was an established and prosperous empire spanning northwest Africa, Iberia, and parts of Italy. Indeed, the Phoenicians continued to bear witness solidarity to their former colony-turned-empire, with Tyre going so far every bit to defy the order of King Cambyses II to canvass against them, which Herodotus claims prevented the Persians from capturing Carthage. The Tyrians and Phoenicians escaped penalty because they had peacefully acceded to Persian dominion years before and were relied upon for sustaining Persian naval ability.[48] Yet, Tyre subsequently lost its privileged status to its principal rival, Sidon. The Phoenicians remained a core asset to the Achaemenid Empire, particularly for their prowess in shipbuilding, navigation, and maritime applied science and skill—all of which the Persians lacked as a predominately land-based power.[47] Archeologist H. Jacob Katzenstein describes the Farsi empire as a "blessing" to the Phoenicians, whose cities flourished due to their strategic and economic importance. He continues:

The Phoenician towns became a strong factor in the evolution of Persian policy because of their fleets and their groovy maritime knowledge and experience, on which the Persian navy depended. The Western farsi king recognized this influential position, and the Persians regarded the Phoenicians more than as allies than subjects. Arvad, Sidon, and Tyre were given large tracts of land and allowed to trade both on the Phoenician and Palestinian coast.[47]

Consequently, the Phoenicians appeared to have been consenting members of the Persian royal project. For example, they willingly furnished the bulk of the Persian armada during the Greco-Persian Wars of the belatedly 5th century BC.[51] Herodotus considers them "the best sailors" amongst Farsi forces.[52] Phoenicians under Xerxes I were as commended for their ingenuity in edifice the Xerxes Canal and the pontoon bridges that allowed his forces to cantankerous into mainland Greece.[53] Withal, they were reportedly harshly punished by the Persian rex post-obit his ultimate defeat at the Battle of Salamis, which he blamed on Phoenician cowardice and incompetence.[54]

In the mid-fourth century BC, Rex Tennes of Sidon led a failed rebellion confronting Artaxerxes III, enlisting the assist of the Egyptians, who were subsequently drawn into a war with the Persians. A detailed business relationship of the rebellion and subsequent conflict was described by Diodorus Siculus.[55] The resulting destruction of the city led once again to the resurgence of its rival Tyre, which remained the principal Phoenician city for 2 decades until the inflow of Alexander the Great.

Hellenistic period (332–63 BC) [edit]

Located on the western periphery of the Farsi Empire, Phoenicia was one of the first areas to be conquered by Alexander the Peachy during his military campaigns beyond southwest asia. Alexander's main target in the Persian Levant was Tyre, now the region's largest and most important city. It capitulated after a roughly vii calendar month siege, during which many of its citizens fled to Carthage.[56] Tyre's refusal to allow Alexander to visit its temple to Melqart, culminating in the killing of his envoys, led to a brutal reprisal: ii,000 of its leading citizens were crucified and a puppet ruler was installed.[57] The rest of Phoenicia hands came under his control, with Sidon, the 2d most powerful metropolis, surrendering peacefully.[46]

A naval action during Alexander the Great'southward siege of Tyre (350 BC). Drawing by André Castaigne , 1888–89.

Unlike the Phoenicians—and for that matter their former Persian rulers—the Greeks were notably indifferent, if non hostile, to strange cultures. Alexander's empire had a policy of Hellenization, whereby Greek culture, religion, and sometimes language were spread or imposed beyond conquered peoples. This was typically implemented through the founding of new cities (well-nigh notably Alexandria in Arab republic of egypt), the settlement of a Greek urban elite, and the alteration of native place names to Greek.[56]

Withal, the Phoenicians were one time again an outlier inside an empire: in that location was evidently no "organised, deliberate try of Hellenisation in Phoenicia", and with i or two minor exceptions, all Phoenician city states retained their native names, while Greek settlement and administration appears to have been limited.[56] This is despite the fact that adjacent areas had been Hellenized, every bit had peripheral territories like the Caucasus and Bactria.

The Phoenicians as well continued to maintain cultural and commercial links with their western counterparts. Polybius recounts how the Seleucid male monarch Demetrius I escaped from Rome past boarding a Carthaginian ship that was delivering goods to Tyre.[58] An inscription in Malta, made between the second and tertiary centuries BC, was dedicated to Herakles/Melqart in both Phoenician and Greek. To the extent the Phoenicians were subject to some caste of Hellenization, "in that location was much continuity with their Phoenician past—in language and perhaps in institutions; certainly in their cults; probably in some sort of literary tradition; perchance in the preservation of archives; and certainly in a continuous historical consciousness."[59] There is even evidence that a Hellenistic-Phoenician culture spread inland to Syria.[sixty] The adaptation to Macedonian dominion was likely aided by the Phoenician'south historical ties with the Greeks, with whom they shared some mythological stories and figures; the two peoples were even sometimes considered "relatives".[61]

Alexander's empire collapsed soon subsequently his death in 323 BC, dissolving into several rival kingdoms ruled by his generals, relatives, or friends. The Phoenicians came under the control of the largest and most powerful of these successors, the Seleucids. The Phoenician homeland was repeatedly contested by the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Arab republic of egypt during the xl year Syrian Wars, coming under Ptolemaic rule in the third century BC.[44] The Seleucids reclaimed the area the following century, property it until the mid-first century BC. Under their rule, the Phoenicians were evidently immune a considerable caste of autonomy.[44]

During the Seleucid Dynastic Wars (157–63 BC), the Phoenician cities were fought over by the warring factions of the Seleucid royal family unit. The Seleucid Empire, which once stretched from the Aegean Bounding main to Islamic republic of pakistan, was reduced to a rump state comprising portions of the Levant and southeast Anatolia. Picayune is known of life in Phoenicia during this time, but the Seleucids were severely weakened, and their realm left equally a buffer between various rival states, before existence annexed to the Roman Republic by Pompey in 63 BC. Afterward centuries of decline, the last vestiges of Phoenician power in the Eastern Mediterranean were absorbed into the Roman province of Coele-Syria.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Sometimes rendered "Wen-Amon"

References [edit]

- ^ KITTO, John (1851). A Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature. Adan and Charles Black.

- ^ Malaspina, Ann (2009). Lebanon. Infobase Publishing. ISBN978-1-4381-0579-vi.

- ^ Aubet (2001), p. 17. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFAubet2001 (help)

- ^ "Phoenicia". Ancient History Encyclopedia . Retrieved 2017-08-09 .

- ^ Quinn (2017), pp. 201–203. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFQuinn2017 (aid)

- ^ R. A. Donkin (1998). Beyond Toll: Pearls and Pearl-angling : Origins to the Age of Discoveries, Volume 224. p. 48. ISBN0-87169-224-4.

- ^ Bowersock, G.W. (1986). "Tylos and Tyre. Bahrain in the Graeco-Roman World". In Khalifa, Haya Ali; Rice, Michael (eds.). Bahrain Through The Ages – the Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 401–two. ISBN0-7103-0112-X.

- ^ Ju. B. Tsirkin. "Canaan. Phoenicia. Sidon" (PDF). p. 274. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-x-10. Retrieved 2013-11-xxx .

- ^ Arnold Heeren, p. 441

- ^ Rice, Michael (1994). The Archeology of the Arabian Gulf. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN0-415-03268-seven.

- ^ Rice (1994), p. 21.

- ^ Haber, Marc; Doumet-Serhal, Claude; Scheib, Christiana; Xue, Yali; Danecek, Petr; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Youhanna, Sonia; Martiniano, Rui; Prado-Martinez, Javier; Szpak, Michał; Matisoo-Smith, Elizabeth; Schutkowski, Holger; Mikulski, Richard; Zalloua, Pierre; Kivisild, Toomas; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2017). "Continuity and Admixture in the Concluding 5 Millennia of Levantine History from Ancient Canaanite and Present-Solar day Lebanese Genome Sequences". American Journal of Human Genetics. 101 (2): 274–282. doi:x.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.013. PMC5544389. PMID 28757201.

- ^ Almarri, Mohamed A.; Haber, Marc; Lootah, Reem A.; Hallast, Pille; Al Turki, Saeed; Martin, Hilary C.; Xue, Yali; Tyler-Smith, Chris (September 2021). "The genomic history of the Eye East". Cell. 184 (xviii): 4612–4625.e14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.013. PMC8445022. PMID 34352227. S2CID 236906840.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1992). "Pastoral Nomadism in Arabia: Ethnoarchaeology and the Archaeological Record—A Instance Study". In Bar-Yosef, O.; Khazanov, A. (eds.). Pastoralism in the Levant. Madison: Prehistory Press. ISBN0-9629110-8-nine.

- ^ Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998), "Canaanites" (British Museum People of the Past)

- ^ Woodard, Roger (2008). The Ancient Languages of Syrian arab republic-Palestine and Arabia. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-68498-9.

- ^ Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. pp. 1–19. ISBN978-0-520-22614-2.

- ^ Stieglitz, Robert R. (1990). "The Geopolitics of the Phoenician Littoral in the Early Iron Age". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Enquiry (279): nine–12. doi:10.2307/1357204. JSTOR 1357204. S2CID 163609849.

- ^ a b c d e f Scott, John (1 April 2018). "The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World". Comparative Civilizations Review. 78 (78).

- ^ Coulmas, Florian, Writing Systems of the Globe, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 1989.

- ^ William H. Barnes, Studies in the Chronology of the Divided Monarchy of Israel (Atlanta: Scholars Printing, 1991) 29–55.

- ^ Ricardo Duchesne, The Uniqueness of Western Civilization (2011), p. 77, www.bibotu.com/books/2012/Th%20e%20Uniqueness%20of%20Western%20Civilization.pdf

- ^ Chamorro, Javier Chiliad. (1987). "Survey of Archaeological Enquiry on Tartessos". American Periodical of Archaeology. 91 (ii): 197–232. doi:x.2307/505217. JSTOR 505217.

- ^ Thompson, Christine; Skaggs, Sheldon (2013). "Rex Solomon'southward Silverish? Southern Phoenician Hacksilber Hoards and the Location of Tarshish". Net Archaeology (35). doi:ten.11141/ia.35.6.

- ^ a b c d east f The Phoenicians: A Captivating Guide to the History of Phoenicia and the Bear on Fabricated past One of the Greatest Trading Civilizations of the Aboriginal World, Captivating History (December.16, 2019), ISBN 9781647482053.

- ^ two Samuel v:11, 1 Kings five:1, and ane Chronicles 14:1. Run into also Book of Isaiah (Isaiah 23), Book of Jeremiah (25:22, 47:iv), Volume of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 26–28), Book of Joel (Joel 3:four–8), and Book of Amos (Amos i:nine–10)

- ^ a b Pritchard, James B., ed. (1978). "2 The Phoenicians: Sources for Their History". Recovering Sarepta, a Phoenician City: Excavations at Sarafand, Lebanon, 1969-1974, by the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. Princeton University Press. pp. fifteen–36. ISBN978-0-691-09378-9. JSTOR j.ctt7zvjcs.7.

- ^ James B. Pritchard, introduction to The Sea Traders, by Maitland A. Edey (New York: Time-Life Books, 1974), p. 7.

- ^ Hoffman, Joel Thousand. (2004). In the first : a brusk history of the Hebrew language. New York, NY [u.a.]: New York Univ. Press. p. 23. ISBN978-0-8147-3654-8 . Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ Fischer, Steven Roger (2004). A history of writing. Reaktion Books. p. 90.

- ^ Markoe (2000), p. 108.

- ^ Zellig Sabbettai Harris. A grammar of the Phoenician language. p6. 1990

- ^ Edward Clodd, Story of the Alphabet (Kessinger) 2003:192ff

- ^ The Evolution of the Greek Alphabet within the Chronology of the I (2009), Quote: "Naveh gives four major reasons why information technology is universally agreed that the Greek alphabet was adult from an early Phoenician alphabet.

1 According to Herodutous "the Phoenicians who came with Cadmus... brought into Hellas the alphabet, which had hitherto been unknown, every bit I think, to the Greeks."

ii The Greek Letters, alpha, beta, gimmel have no meaning in Greek but the meaning of most of their Semitic equivalents is known. For instance, 'aleph' ways 'ox', 'bet' means 'business firm' and 'gimmel' ways 'throw stick'.

iii Early Greek letters are very like and sometimes identical to the West Semitic letters.

4 The letter sequence betwixt the Semitic and Greek alphabets is identical. (Naveh 1982)" - ^ Markoe (2000) p. 111

- ^ Coulmas (1989) p. 141.

- ^ The engagement remains the subject of controversy, co-ordinate to Markoe, Glenn E. (1990). "The Emergence of Phoenician Art". Message of the American Schools of Oriental Inquiry (279): 13–26. doi:10.2307/1357205. JSTOR 1357205. S2CID 163353156. p. 13. "Most scholars have taken the Ahiram inscription to engagement from around 1000 B.C.E.", notes Melt, Edward Yard. (1994). "On the Linguistic Dating of the Phoenician Ahiram Inscription (KAI 1)". Periodical of About Eastern Studies. 53 (one): 33–36. doi:10.1086/373654. JSTOR 545356. S2CID 162039939. Cook analyses and dismisses the appointment in the thirteenth century adopted by C. Garbini, "Sulla datazione della'inscrizione di Ahiram", Annali (Istituto Universitario Orientale, Naples) 37 (1977:81–89), which was the prime source for early on dating urged in Bernal, Martin (1990). Cadmean Letters: The Transmission of the Alphabet to the Aegean and further West earlier 1400 BC. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN978-0-931464-47-8. Arguments for a mid 9th-8th century BCE engagement for the sarcophagus reliefs themselves—and hence the inscription, too—were fabricated on the basis of comparative art history and archaeology past Porada, Edith (1 Jan 1973). "Notes on the Sarcophagus of Ahiram". Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society. 5 (1): 2166. ; and on the basis of paleography among other points by Wallenfels, Ronald (ane January 1983). "Redating the Byblian Inscriptions". Periodical of the Ancient Well-nigh Eastern Society. xv (one): 2319.

- ^ "Phoenicia | historical region, Asia". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2017-08-09 .

- ^ Gerhard Herm, The Phoenicians, trans. Catherine Hiller (New York: William Morrow, 1975), p. eighty.

- ^ Gerhard Herm, The Phoenicians, trans. Catherine Hiller (New York: William Morrow, 1975), p. 80.

- ^ Karl Moore and David Lewis, Birth of the Multinational (Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business organization School Press, 1999), p. 85.

- ^ Piero Bartoloni, "Ships and Navigation," in The Phoenicians, ed. Sabatino Moscati (New York: Abbeville, 1988), p. 76.

- ^ a b c "Lebanon – Assyrian and Babylonian domination of Phoenicia". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2020-04-22 .

- ^ Bondi, South.F. (2001), "Political and Administrative Organization," in Moscati, S. (ed.), The Phoenicians. London: I.B. Tauris.

- ^ a b Stephen Stockwell, "Before Athens: Early Pop Government in Phoenician and Greek City States," Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 2 (2010): 128.

- ^ a b c d Jacob Katzenstein, Tyre in the Early Western farsi Period (539-486 B.C.E.) The Biblical Archeologist, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Winter, 1979), p. 31, www.jstor.org/stable/3209545.

- ^ a b Herodotus. The Histories, Book Iii. pp. §nineteen.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories, Volume Three. pp. 218, §91.

- ^ MAMcIntosh (2018-08-29). "A History of Phoenician Culture". Brewminate . Retrieved 2020-04-20 .

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories, Book Five. pp. §109.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories, Book Five. pp. §96.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories, Book Vii. pp. §23.

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories, Book VIII. pp. §90.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Diodorus Siculus — Book XVI Chapters 40‑65". penelope.uchicago.edu . Retrieved 2020-04-twenty .

- ^ a b c Fergus Millar, The Phoenician Cities: A Case-Study of Hellenisation, University of N Carolina Press (2006), pp. 32–fifty, www.jstor.org/stable/ten.5149/9780807876657_millar.eight

- ^ "Alexander'south Siege of Tyre, 332 BCE". World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved 2019-03-07 .

- ^ Fergus Milla, The Phoenician Cities: A Case-Written report of Hellenisation, University of North Carolina Press (2006), pp. 36–37, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807876657_millar.8

- ^ Millar, The Hellenistic World and Rome, p. 40: "It does, nonetheless, accept some significance, if only illustrative, that at least some Phoenicians abroad continued to compose and inscribe texts in Phoenician. At Demetrias, for example, iii men from the third century, all with Greek names— i from Sidon, one from Arados, and one from Kition—take left brief inscriptions in Phoenician. In Athens we have a bilingual Greek-Phoenician inscription giving a fine example of equivalence, or semi-equivalence, in theophoric names."

- ^ Millar, p. 34: "Phoenician culture seems in some sense to have spread inland also every bit overseas in the Hellenistic menstruation, as Punic culture did besides in North Africa afterward This fact brings Phoenician culture into connectedness with the familiar miracle of the fusion of Greek and not-Greek deities in Syria, or alternatively the survival of non-Greek cults in a Hellenised surround. At that place is nowhere where it appears more vividly before us than in Herodian's description of the cult of Elagabal at Emesa; what is significant is that Herodian idea that ''Elagabal'' was a Phoenician name and that Julia Maesa was '"by origin a Phoinissa""

- ^ Millar, p. fifty: Secondly, and more important, when the Phoenicians began to explore the storehouse of Greek culture, they could notice, amongst other things, themselves, already credited with artistic roles—not all of which, equally it happens, were purely legendary. If some aspects were simply fable, like the story of Kadmos, what is articulate is that the Phoenicians adopted it (perhaps, similar the legend of Aeneas in Italia, very early) and fabricated it their own. In doing and then they acquired both an extra by and a reinforcement of their historical identity; and they also simultaneously gained acceptance equally beingness in some sense Greeks

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Phoenicia

0 Response to "Phoenician Art Particularly Was Among the Most Sought After in the Ancient World"

Post a Comment